Though nowadays within the east Bristol suburbs, Kingswood was once an industrious village at the heart of the local boot and shoe making industry.

Brothers William and Edward Douglas moved here from Greenock in the 1870’s, and by 1882 the Douglas Engineering company was offering everything from bootmaking machinery repairs to blacksmith services. Manufacture of small metal castings followed in the 1890’s, a service one John Joseph Barter, designer of a single cylinder motor-assisted bicycle, used to obtain parts for his new 200cc flat-twin engine.

Mr Barter’s company, Light Motors Ltd, failed in 1906 – after which the brothers were somehow persuaded to purchase the remnants, and employ Mr Barter. Within a year the first Douglas-badged motorcycle had appeared, belt driven and with the flat-twin engine now displacing 350cc – though a two-speed gearbox was available in time for three machines to compete in the 1911 Isle of Man Junior TT race.

Two finished, with William Douglas himself in seventh place – and the 1912 event saw Douglas machines finish first, second, and fourth. Reliability became a byword, sales climbed quickly – and supply contracts for the 1914-16 war effort followed, though production estimates vary wildly – between 25,000 and 70,000 machines.

During and after the Great War, Douglas dabbled in light cars. In 1914, a 9 horsepower twin cylinder version was listed at just £175, but by 1920 the standard two seater, now with a 10½ horsepower engine, cost £450. Douglas gave up on motor cars in 1922 with a few hundred examples apparently completed – and no known survivors today.

Motorcycles proved more successful, with 1923 proving the company’s greatest year, when a Douglas equipped with a very early disc front brake and innovative “banking” sidecar won the first Isle of Man Sidecar TT race outright, ridden by Freddie Dixon, with passenger Walter Denney. The sidecar design was Dixon’s invention, and after retiring from motorcycle sport in 1928 he briefly worked as a designer for Douglas before embarking on a highly successful car racing career, scoring several successes at Brooklands.

Then, 1923 also saw Douglas motorcycles win the prestigious Isle of Man TT 500cc Senior category, the Welsh TT, the Spanish 12-hour race and the French Grand Prix. Remarkable endurance was also vividly demonstrated when a 2¾ horsepower Douglas averaged over 43 mph to win the demanding 430 mile Durban-Johannesburg Race. These competition machines were modified for Sprint, dirt track and speedway racing, the model line ultimately developing a unique niche and enjoying a legendary reputation.

During the 1920’s Douglas held a Royal Warrant for motorcycle supplies to Prince Albert, which was retained when he later ascended the throne as King George VI: Machines were also supplied to the Spanish Royal household. However, the 1920’s recession exposed the company’s weak financial position, and in 1932 the Douglas family relinquished control.

New management continued motorcycle production and began diversification, but voluntary liquidation followed in 1935. Aeronautical investment company The British Pacific Trust stepped in, registering Aero Engines Ltd at Kingswood, vowing to end ‘unprofitable’ motorcycle manufacture, and make aircraft engines and parts instead. Details here become hazy, but as World War II began, two things were clear: aviation-related products were being made – and Douglas motorcycle manufacture never ceased.

Kingswood’s wartime production included aircraft parts, water pumps, stationary engines and generator sets – though apparently not motorcycles. A final, overhead valve development of the 350cc flat twin engine became the standard wartime power unit – later appearing in the T35, the first post war motorcycle.

Following more fundraising, just over 2000 examples of this were built by yet another new company – Douglas (Kingswood) Ltd, established in 1946. The same engine also powered the T35 replacement and final production Douglas motorcycle, the Dragonfly, a quite advanced machine offered from 1955.

Douglas advertising from the immediate post war years reveals remarkable diversification, apparently to maintain viability. Aside from motorcycles, products included single and twin cylinder stationary engines, industrial power trucks, generator sets, electric delivery vehicles – even petrol powered milk floats, of which one example from the handful built survives.

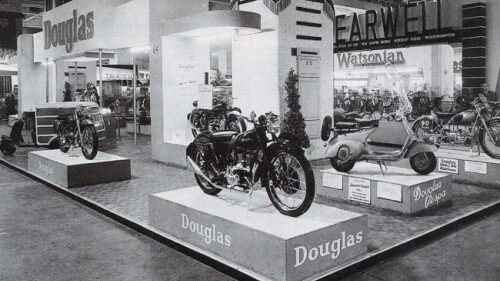

During 1949, as bankruptcy edged closer, Douglas was licensed by Italian manufacturer Piaggio to make Vespa scooters for sale in Britain and Commonwealth countries. Hindsight suggests that long term underfunding caused ongoing, never fully resolved Vespa production and marketing difficulties at Kingswood – and delayed the start of production until April 1951, when some accounts suggest Douglas was already in receivership.

Whether Piaggio appreciated the financial situation is unclear, but as worldwide Scooter sales rose rapidly, correspondence exists suggesting their mistake was eventually recognised. The restricted market share achieved in key territories – especially Britain – because of production shortages allowed deadly rivals Innocenti to make big inroads with their Italian-built Lambretta.

Despite the financial challenges, virtually all early Vespas sold in Britain were built at Kingswood, where most mechanical parts were also made. Panelwork came from Pressed Steel, with other British companies supplying everything from tyres to electrical items. Figures held by Britain’s veteran Vespa club suggest the 11 acre Bristol site – though simultaneously involved in contract work for Bristol Aircraft – produced over 126,000 Vespas, the only place in Britain where scooters were ever built in volume. After production ended in 1965, Douglas continued to import Vespa scooters and later small Gilera motorcycles until 1982, when the sales and service operation was closed.

In 1955 Douglas was taken over by the vast Westinghouse Brake and Signal operation – though the anticipated financial salvation never materialised. Westinghouse had no interest in motorcycles, simply wanting facilities to sub-contract brake equipment production from its Chippenham headquarters. Finance for Vespa production remained tight – and the last Douglas-branded motorcycles were made in 1957.

Today, though the once-famous name lingers on a Kingswood road and industrial estate, all that remains are fading memories, and some treasured historic motorcycles – all now 60 years old or more.

References

Wikipedia entry for Douglas motorcycles:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Douglas_(motorcycles)

A brief history of Douglas motorcycles and some pictures of its products:

http://www.gracesguide.co.uk/Douglas

An alternative brief history of Douglas motorcycles:

http://www.britishclassicmotorcycles.com/Douglas.html

The Douglas motorcycle club website:

from http://www.douglasmcc.co.uk/

Complete list of Douglas motorcycle models:

www.douglasmcc.co.uk/douglas-motorcycles-1907-1957/models

Wikipedia entry for Vespa scooters:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vespa

Plenty about the Vespa story – at Bristol and beyond is here:

http://www.veteranvespaclub.com

Aerial pictures of the Douglas Kingswood site in 1926 are here:

http://www.britainfromabove.org.uk/image/epw016942?quicktabs_image=1#quicktabs-image

History of the Kingswood area:

www.kingswoodhistorysociety.org/interesting-local-history

Map of the Kingswood area:

http://www.mykingswood.co.uk/kingswood/map

Later history of the Douglas factory operation at Kingswood:

www.polunnio.co.uk/research-resources/constituent-companies/douglas-kingswood

Wikipedia entry for Freddie Dixon:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Freddie_Dixon

Official Isle of Man TT races website – direct link to competitors and winners: database

https://www.iomtt.com/TT-Database/competitors.aspx?ride_id=168&filter=D

Publications relating to Douglas motorcycles and the company history:

The Douglas Motorcycle – The Best Twin (Revised and Enlarged Edition) Jeff Clew, (1981) Haynes Publishing. ISBN 0-85429-299-3.

The Illustrated History of Douglas motorcycles. Harold Briercliffe and Eric Brockway. (1991) Haynes Publishing. ISBN 0-85429-799-5.

Douglas Light Aero Engines – from Kingswood to Cathcart. Brian Thorby (2010) Redcliffe Press. ISBN 978-1-906593-25-4.

Documents the surprisingly extensive involvement of Douglas in light aircraft engine manufacture

Douglas -The Complete Story Mick Walker. (2010) The Crowood Press

ISBN 978- 184797-197-5.

Ride it – the complete book of Speedway. Cyril May. (1976) Haynes Publishing.

Freddie Dixon: The Man with the Heart of a Lion. – David Mason (2008) Haynes Publishing. ISBN 1 844 2554 09

© Dave Moss

Dave Moss has a lifetime connection with the world of motoring. His father was a time-served skilled engineer from an age when car repairs really meant repairs: he ran his own garage from the 1930's to the 60's, while Mum was the boss's secretary at a big Austin distributor. Both worked their entire lives in the motor trade, so if motor oil's not in Dave's blood, its surely a very close thing.

Though qualified in Electronics, for Dave it seemed a natural step into restoring a succession of classic cars, culminating in a variety of Minis. Writing and broadcasting about these, and a widening range of motoring matters ancient and modern, gathered pace in the 1970's and has taken over since. Topics nowadays range across the modern motoring mainstream to the offbeat and more arcane aspects of motoring history, and outlets embrace books, websites national and international magazines, newspapers, radio programmes, phone-ins and guest appearances. Spare time: hard graft on the garage floor attending to vehicles old and new. Latest projects: that 1968 Mini Cooper S has finally moved again after 30 years, and when the paint is finished, the 1960 Morris Mini 850 will also soon be ready for the road again...