Britain’s success in WW2 is partly down to a little known role undertaken with the strictest secrecy in thewesterngroup area, writes Dave Moss.

What is more, it is probably strange to realise that today’s global in-car entertainment and information industry has its roots much closer to home, and with the same company which brought Britain victory in the armed conflict.

In 1922, Eric Kirkham Cole set up business on his own account making radio sets, for which demand was booming following the opening of the BBC.

In a small room in Westcliff on Sea, helped by future wife Muriel Bradshaw, production reached five or six units a week. Powered by heavy, expensive and inconvenient rechargeable batteries, Eric Cole was soon inspired to design a so-called battery eliminator, allowing their radios to work from the mains supply.

This proved highly successful, and in 1926 the business was reorganised as E.K.Cole Ltd, from which sprang the brand name “Ekco.” Continuing success saw the company quoted on the Stock Exchange, and new factories built to allow rapid expansion in what was to prove the golden age of radio.

With demand for radio receivers booming, in the 1930’s Ekco dared to be different from its competitors, abandoning then-typical all-wood radio cabinets. Instead they used Bakelite, an early type of plastic, which could be moulded into shapes not easily achievable in wood.

It was a gamble requiring heavy investment and high production volumes for viability, but it worked: demand for Ekco radios in attractive art-deco period Bakelite cabinets rapidly rose.

In 1935 the company began researching what we now know as radar technology – with the government becoming closely involved as war clouds gathered. Radar development was based at Ekco’s Southend headquarters, hardly ideal for radio and radar research or production when war with Germany was declared, being well within bombing range.

Ekco’s sensitive facilities were thus dispersed to less prominent and more distant areas, ranging from Aylesbury to Rutherglen, east of Glasgow.

With war drawing closer, Malmesbury in Wiltshire also joined Ekco’s empire when £6500 was expended at auction to purchase Cowbridge House and most of its estate, including an electricity-generating Mill.

The property, just outside the town on the main Swindon road – nowadays the B4042 – was chosen as the top-secret design and production centre for airborne intercept (AI) and anti-surface vessel (ASV) radar systems.

Major alterations to the house itself and much external building work to provide factory space rapidly followed. Further premises – informally known as the “Western Development Unit” – were rented in the town itself, where more top-secret design work resulted in the VHF fighter control system successfully deployed in the Battle of Britain. At its height, over 1000 people were employed on Ekco’s wartime work in Malmesbury.

After the war, design and manufacture of military radar and radio equipment was gradually moved elsewhere, with Cowbridge House turned over to domestic equipment manufacture.

Following Ekco’s 1950’s takeover of the Ferranti and upmarket Dynatron consumer brands, this first centred on radio and TV sets, tubular heaters and now forgotten “radiograms.”

Ekco had produced its first car radio as far back as 1934, a heavy, three-section unit, with vibrator-driven power pack to operate the valves it contained.

Weight, bulk, cost and power consumption ensured these devices left pre-war British motorists distinctly unimpressed, but by 1949, slightly more compact units were becoming available. With radio then the primary news and entertainment medium, Ekco car radios were fitted by several British car makers including Daimler, Ford and Bristol.

The same units – still with separate power supply – could be bought retail with fitting kits suiting cars, coaches and commercial vehicles. A typical early 1950’s self-fit Ekco car radio cost around £30, including 33% purchase tax – and needed an annual £1.0s.0d. licence.

Sales were slow until the breakthrough arrival of transistors in the mid 1950’s, with Pye Electronics’ subsidiary, Newmarket Transistors, one of the earliest UK suppliers .

Replacing big valves with tiny transistors finally made single-unit car radios genuinely practical for dashboard fitment – and unsurprisingly, Pye led the way in building them.

Prices tumbled: in 1959 a basic all-transistor manually-tuned Pye car radio cost 18 ½ guineas (about £18.52p) including tax, which left Ekco very well placed when the company merged with Pye in 1960.

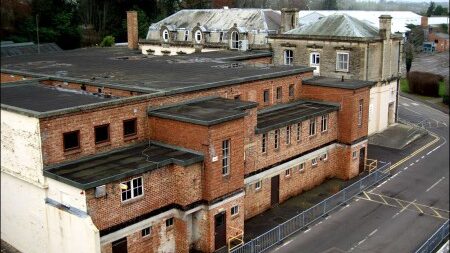

COWBRIDGE HOUSE – Its reputed neither locals or the workforce peaking around 1000 people knew exactly what was being made at Cowbridge House during the second World War.

Post war operations were less secretive and at least as productive, but an abortive 1960’s merger saw Ekco fall on hard times. Following a takeover by the Philips group a succession of owners ranging from TMC to AT&T further extended on site buildings, and began telephone system design and manufacture. Once familiar products including the BT Herald and Statesman phone systems were designed here, though like the old British motor industry, the British telephone industry also came to a sad end.

In the early 2000’s Lucent Technologies sold off the site, which became derelict. In a melancholy state of disrepair, Cowbridge House opened its doors for the last time as part of a September 2004 Heritage Weekend. Its ugly but expedient wartime extensions then remained, down to forlorn, overgrown and never-used defensive pill-boxes outside – though the old Shadow factory buildings and once-ornate Italian gardens and neatly kept lawns were gone. Internally, key elements of the original design survived – but, inside and out, what remained was too far down the road to ruin for resurrection to be realistic.

Any secrets held by Cowbridge House then will remain secrets forever. Standing for over 250 years and once the seat of Samuel Bendry Brooke of the wealthy family behind Brooke Bond Tea, until 1938 it was a luxurious family home in 14 acre grounds. In 2007 it was demolished to make way for new housing, and perhaps surprisingly, little now remains which hints at the events of years gone by.

Looking back, the production of thousands of car radios which tuned into the sounds of the sixties and entertained a generation of car owners born in the aftermath of war might seem of little consequence. But… around Malmesbury, many today remain convinced the second world war was won in part by the radar equipment designed and produced entirely at Cowbridge House.

No time was then lost putting a new “transistorised” car radio range into production, initially with separate identities, and sales through separate marketing channels.

However by 1962 it was hard to ignore a certain visual similarity between basic and push-button de-luxe car radios from Ekco and Pye – even if their prices were slightly different. Clearly 1960’s badge engineering was not entirely confined to British car manufacture.

In 1959 Pye estimated there were about 4m cars on British roads – but only around 400,000 had a radio. In the early 1960’s, this provided an opportunity fully exploited by the newly merged companies – and Cowbridge House became Ekco’s car radio manufacturing centre. Chances are if your family had a car built between 1960 and 1968 with an aftermarket radio, that unit was probably built – and could have been designed – at Malmesbury.

Unfortunately the merger was unsuccessful for reasons unconnected with car radio, marking the beginning of the end for Ekco. Eric Cole resigned in 1961 following a boardroom disagreement, and died in 1965. By 1966 the troubled combine was desperately seeking a buyer, just as car audio profitability collapsed under intensifying international competition.

In 1967 the vast Philips Group took over, expanding its already major Europe-wide interests in consumer and industrial electronics. It already had a vast car audio division.

The last radio and TV equipment left Cowbridge House in 1968, and inside two years the Ekco name had moved into history. Yet the car radio demand Ekco and Pye jointly developed, exploited and abandoned in a few short years was huge – witness the fact that of the many high profile electronics avenues pursued in its 40 year existence, it was the closure of the car radio repair workshop in 1977 which marked the final disappearance of the Ekco brand from public view and history tuned off this piece of automotive development.

© Image Terry Thomas

Further reading:

You can read more of lost heritage by Bob Browning.

Wiltshire Council has a reference as well.

An Ekco advert appeared in Autocar in 1949 and another produced for the 1951 motor show.

Dave Moss has a lifetime connection with the world of motoring. His father was a time-served skilled engineer from an age when car repairs really meant repairs: he ran his own garage from the 1930's to the 60's, while Mum was the boss's secretary at a big Austin distributor. Both worked their entire lives in the motor trade, so if motor oil's not in Dave's blood, its surely a very close thing.

Though qualified in Electronics, for Dave it seemed a natural step into restoring a succession of classic cars, culminating in a variety of Minis. Writing and broadcasting about these, and a widening range of motoring matters ancient and modern, gathered pace in the 1970's and has taken over since. Topics nowadays range across the modern motoring mainstream to the offbeat and more arcane aspects of motoring history, and outlets embrace books, websites national and international magazines, newspapers, radio programmes, phone-ins and guest appearances. Spare time: hard graft on the garage floor attending to vehicles old and new. Latest projects: that 1968 Mini Cooper S has finally moved again after 30 years, and when the paint is finished, the 1960 Morris Mini 850 will also soon be ready for the road again...