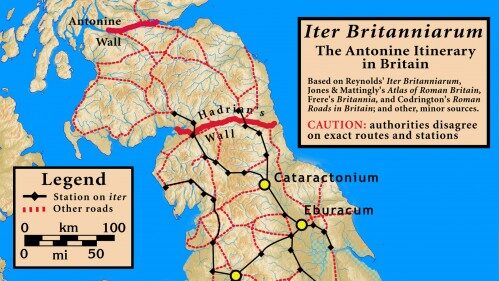

The ‘Antonine Itinerary’ is a register credited to the Roman Emperor Antonini Augusti, believed to date from around 300AD, which maps stations and distances along Britain’s Roman roads.

Some say it contains remarkable coincidences when compared to aspects of today’s English motorway network, and it does indeed show the M4 route from Londinium all the way to Moridunum, (Carmarthen) along with lines of many parts of today’s M2 and M40, the M5, M6… and more.

Of course the Romans preferred straight roads, plenty of today’s towns have Roman roots – and plenty of our non-motorway roads follow the line of Roman predecessors, so maybe it is all just coincidental. But maybe, just maybe, the Romans started the chariot wheels rolling on ideas for Britain’s motorway age, which began unfolding a mere 1600 years later.

The motor-car’s arrival prompted private individuals, encouraged by the proliferation of new railways, to seek parliamentary powers for their very own roads. Importantly for our story, some of these were conceived for limited types of traffic, the key principle underpinning today’s motorway network.

Only a handful – including one in the west-country – gained approval, before the establishment of the Ministry of Transport in 1919 eventually ended privateer road building attempts.

However, it wasn’t until 1936 that the new Trunk Roads Act gave the Ministry full control of some 4500 miles of principal through roads – a figure significantly extended later on. These were defined as “trunk routes,” and the ministry promptly began detailed surveys of every single one…

Seemingly oblivious to the dawn of the motorway age in Italy in 1924 and Germany in 1931, intense planning and design work followed – aimed at building bypasses and making improvements wherever felt necessary.

However the Act prompted the forthright Institute of Highway Engineers to unveil an audaciously ambitious plan for a new, 2,800-mile fast main road network – more than Britain’s motorway mileage even today.

Then, in September 1937, road construction pressure group the British Roads Federation invited over 200 influential personnel to tour the German Autobahn system. Ministry staff were barred from this “German Roads Delegation,” but – politics of the time aside – many MP’s and County highways staff came away very impressed. Afterwards the influential County Surveyors’ Society resolved to pursue construction of a British motorway system rather than support the Ministry proposals.

This series of events softened British government attitudes to motorways, helped further in May 1938, when the Surveyors’ Society released a more realistic plan for a 1000 mile motorway network – at a time when Britain reportedly had a total of just 19 miles of dual carriageway road… Shortly afterwards the Transport Minister – probably attempting appeasement of the growing pro-motorway lobby – tentatively proposed an ‘experimental’ north-south motorway in Lancashire. The Ministry, however, stuck doggedly to its vast long term programme of main road improvements. At the outbreak of war in 1939, work was planned for 30 main routes, with 100 schemes already approved, at a cost estimated even then at almost £200m – equating to about 50 years’ work at the proposed annual expenditure levels.

Motorways did not feature anywhere: maybe heads were stuck defiantly in the sand, but the war lowered the curtain on this farrago with just a handful of schemes completed.

A particularly interesting aspect of the British motorway story is that much of the major change in mindset needed to pave the way for a future network occurred during the war. The need to move servicemen, supplies and protect the UK saw a lot of road building to ports and camps as well as new airfields.

It’s known that by 1942 outline Ministry proposals existed for several all-new high speed routes. One linked London to Birmingham, Lancashire and Scotland, with a branch to Coventry, routing onward to Leeds.

Another extended the existing Liverpool-Manchester road (below) eastward to Leeds and ultimately Hull, while a Birmingham motorway ring avoided Solihull, Wolverhampton and Walsall, and joined a northbound link from Bristol. Narrow and full gauge railways were used to transport materials to the site.

By the end of the war, officialdom had moved on from the concept of disconnected bypasses and unlinked road improvements, seeing future economic prosperity in new, purpose built, higher speed, longer distance roads. Its widely held that a 1942 report on the value of motorways written by the Ministry’s Chief Highways Engineer Sir Frederick Cook was especially influential, reinforced months later by a “Report on Highway Development in the immediate Post War Years,” by Cumberland County Surveyor G.O. Lockwood.

Together, these documents are credited with persuading the War Cabinet and its Reconstruction Policy and Priorities Committees to adopt a post-war principle of motorway construction.

An announcement that almost 800 miles of motorway would be built came soon after the war… without saying where or when… This was largely because legislation did not then allow for roads carrying only specific types of traffic.

After three years of manoeuvring, the 1949 Special Roads Act provided this power, but motorways weren’t a priority in an age of austerity. Then, in 1950, petrol rationing ended, new cars began to appear, and the new Conservative government came under pressure to improve roads.

The mid-1950’s saw road building cash finally released – and Lancashire County Council, Britain’s earliest official motorway advocate, rejoiced with news that work on the Preston bypass motorway – drawn up during the war as part of that ethereal north-south motorway plan – could start in 1956.

Harold Watkinson was appointed transport minister that same year, swiftly ordering a Trunk road review and 20 to 30 year master plan, including updated motorway proposals. Published in 1960, the plan was wholeheartedly adopted by Government, including its commitment to 1,000 miles of motorway by the 1970’s.

Watkinson kick-started this huge programme in July 1957, announcing routes from London to Birmingham and the north west, to Dover, and South Wales, along with links from Bristol and south Wales to Birmingham.

Britain’s motorway age finally dawned in December 1958, when Prime Minister Harold MacMillan opened the 8.26 mile Preston bypass; the first 67 miles of the new London to Birmingham motorway followed in November 1959.

References and bibliography

Detailed Wikipedia article on the Antoine Itinerary:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antonine_Itinerary

Review of a 1949 book, Roadway to Recovery, (saying motorways will save money) by Christopher T Brunner, of the British Road Federation, is here (on p27 of PDF)

http://www.concretecentre.com/pdf/CQ_005_Spring1949.PDF

There are details of the 1949 Special Roads Act here:

http://www.sabre-roads.org.uk/wiki/index.php?title=Special_Road

and more information here:

http://pathetic.org.uk/features/special_roads/

The full unexpurgated original 1949 Special Roads act can be viewed here

http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1949/32/enacted

The Institute of Highway Engineers offers a timeline lookback at the history of road building since 1920, including motorways, with some archive pictures – here:

http://www.theihe.org/about-us/ihe-at-50/milestones/

Motorways are “controlled access roads” which are surprisingly common around the world. The story is here:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Controlled-access_highway

There is an insight into early background to the British Motorway network here

and here

The story of how the Preston bypass came to be built is here:

http://www.cbrd.co.uk/articles/preston-bypass/01.shtml

A copy of the leaflet issued at the inauguration ceremony for the Preston bypass, carried out by Minister of Transport and Civil Aviation Harold Watkinson on June 12th 1956, is here:

http://www.cbrd.co.uk/articles/preston-bypass/01.shtml

A copy of the leaflet issued at the opening of the Preston bypass, carried out by Prime Minister Harold Macmillan on December 5th 1958, is here:

http://www.cbrd.co.uk/articles/opening-booklets/pdf/prestonbypass.pdf

Exactly how the German autobahn network came into existence is here

http://www.dw.com/en/the-myth-of-hitlers-role-in-building-the-autobahn/a-16144981

The Wikipedia entry for German Autobahns is here

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Autobahn

Books

Anderson R.M.C. (1932), The Roads of England, Ernest Benn, London.

Baldwin P. & Baldwin R. (2004), The Motorway Achievement, Thomas Telford,

London.

Bressey C. & Lutyens E. (1938), Highways Development Survey (Greater

London), London, HMSO.

Gregory J. W. (1938), The Story of the Road, Adam and Charles Beck, London.

Oliver J, (1936), The Ancient Roads of England, Cassell, London.

Plowden W (1971), The Motor Car and Politics 1896 – 1970, The Bodley Head,

London.

Rees Jeffreys W. (1949), The King’s Highway, The Batchworth Press, London.

© Dave Moss

Dave Moss has a lifetime connection with the world of motoring. His father was a time-served skilled engineer from an age when car repairs really meant repairs: he ran his own garage from the 1930's to the 60's, while Mum was the boss's secretary at a big Austin distributor. Both worked their entire lives in the motor trade, so if motor oil's not in Dave's blood, its surely a very close thing.

Though qualified in Electronics, for Dave it seemed a natural step into restoring a succession of classic cars, culminating in a variety of Minis. Writing and broadcasting about these, and a widening range of motoring matters ancient and modern, gathered pace in the 1970's and has taken over since. Topics nowadays range across the modern motoring mainstream to the offbeat and more arcane aspects of motoring history, and outlets embrace books, websites national and international magazines, newspapers, radio programmes, phone-ins and guest appearances. Spare time: hard graft on the garage floor attending to vehicles old and new. Latest projects: that 1968 Mini Cooper S has finally moved again after 30 years, and when the paint is finished, the 1960 Morris Mini 850 will also soon be ready for the road again...