Northern and western parts of Britain’s vast and beautiful south west peninsula have been a tourist magnet since before the turn of the 20th century, initially driven by the coming of railway connections from more industrialised parts of the country.

Then the motor car arrived… and its numbers grew, but with little accompanying improvement to the region’s time-consumingly poor road network.

The 1960’s Beeching-inspired railway cuts left a solitary single track branch to Barnstaple from Exeter – and with few compensatory road improvements, Beeching’s legacy was a wide, picturesque area left to suffer twenty years of stifled growth, restricted development, and dwindling tourist numbers.

The official opening of the A361 North Devon Link Road between the M5 motorway and Barnstaple on July 18th 1989 changed that forever, invigorating the area with a long lost sense of purpose, opening uncharted doors for business and tourism.

It unlocked a new phase of regional development, led by several major industrial and retail names – but even by those standards, an outline application which arrived at North Devon Council offices on the 24 February 1989 was quite unprecedented.

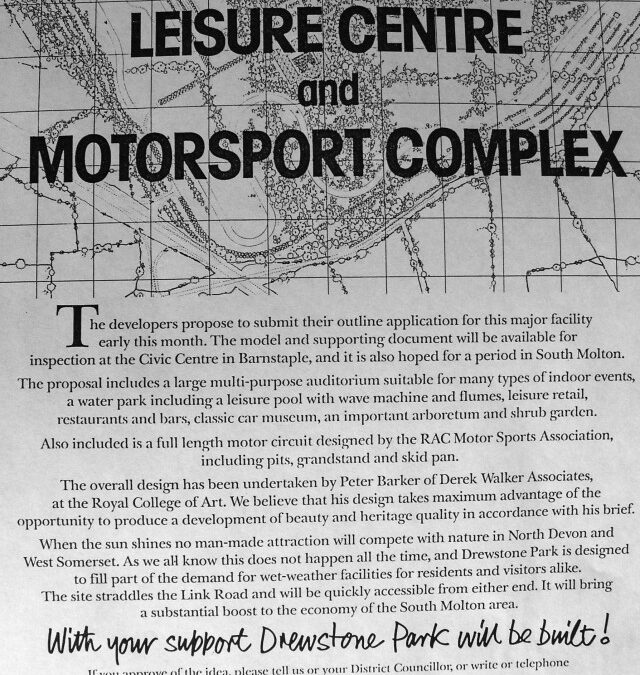

It proposed a motor racing circuit and vast leisure complex named Drewstone Park, sited in undeveloped open countryside midway along the new road, outside – in planning parlance – the “regional sub-centre of South Molton.”

At the time, this small town’s economy depended mostly on services appropriate to the surrounding agricultural area, whose principal claim to fame has long been the densest population of sheep in Britain.

You can almost hear the apocryphal sharp intake of breath in the planning office, echoing distantly down the corridors of time. The west country has many leisure amenities, but even today there is nothing of remotely similar scope to that of the 160 acre site envisaged in this plan. Its central focus was the first purpose-built motor racing circuit to be laid in Britain since before the second world war, meeting Formula 3000 standards and designed by RAC Motor Sports Association officials.

Four adjustable circuit formats were included for the 2.17 mile track, along with a full scale grandstand and state of the art pit facilities, safety and noise abatement measures, all built with extensive integrated landscaping, retaining existing fine woodland within its layout.

The circuit was clearly the jewel in the crown, though it was but one aspect in the wider site, whose overall design was the responsibility of the Architecture Professor at the Royal College of Art.

The complex was visualised with ‘destination’ status, necessary for year-round viability in a location many miles from major population centres. Proposed facilities included a leisure park developed over five years, ‘of a quality as yet little seen in this country…’ an indoor water park, a multi-use auditorium, multi-screen cinema, resource centre and heritage museum, even an under-cover luge run… plus an arboretum eventually to become of national importance, a motocross circuit, skid pan, tyre testing facility and a vehicle restoration centre… and the inevitable restaurants and retail outlets.

Bets were hedged on finance. ‘The funding of leisure schemes is a relatively new activity in the British financial markets,’ said the explanatory information deviously, ‘but some experience elsewhere has shown a reluctance of the city to regard buildings and land limited to leisure use by planning restrictions as security for lending…’ Your correspondent has recently spoken to the surviving scheme partner, and understands costs of around £100m were anticipated – at 1988 prices.

A wave of protest followed the lodging of the application. The site was within a stone’s throw of Exmoor, a national park since 1954, and one of Britain’s most precious and quiet landscapes.

Then as now, local people and conservation groups alike were understandably, ahem, sensitive towards suggestions of major development in, around or near Exmoor, and forces were quickly mobilised.

Two months to the day after the application was submitted, the growing furore reached the columns of The Times newspaper, which reported “…600 letters of complaint had bombarded the council offices in Barnstaple…” The paper’s environment correspondent wrote of “…a storm of opposition from residents, fearful that the scheme would involve noise, traffic and unwanted development.’

Three local parish councils were reportedly ‘overwhelmingly hostile,’ and a member of both South Molton Town Council and North Devon District Council claimed they were “completely and utterly against these proposals…”

Conservation bodies lined up in vehement opposition: “My reaction is a mixture of outrage and astonishment” the then-chairman of the Exmoor Society told the paper.

The Council for the Protection of Rural England reportedly described the scheme as ‘absolutely disastrous’ while the now defunct Countryside Commission claimed it was ‘utterly inappropriate.’

The scheme’s lead partner reportedly dismissed the protests initially as “…a lot of fuss about nothing,” and, when asked by the paper if ‘he did not think the scheme was, at the least, out of character,’ he seemed in no mood for compromise, apparently replying “People who say that do not know what they are talking about.”

The report was later referred to the Press Council, which The Times stated “did not find the article significantly inaccurate or misleading…” A complaint that it constituted an unwarranted personal attack on the scheme’s promoter was also not upheld.

Press advertising in the region failed to allay – or even offset – fears expressed ever more deeply as time passed… and ultimately things turned ugly.

When members of the promoters’ family allegedly began receiving personal threats, the partners pulled the plug. The application was withdrawn on 21 February 1990; tranquillity returned to this most beautiful area, and any thoughts of motor racing in north Devon forever evaporated into the ethereal Exmoor mists…

References

North Devon District Council – Planning Department.

Application No 8300, received 24 February 1989.

The Times newspaper, Monday, 24 April, 1989

‘A property developer is seeking planning permission for a Formula One motor racing circuit on the edge of the Exmoor National Park.’

Author: Michael McCarthy, Environment Correspondent

The Times newspaper- Monday, November 20, 1989

‘Race track report complaint quashed – Exmoor’

Background material relating to the A361 North Devon Link road since opening in 1989:

http://www.devon.gov.uk/countrymile-dontgetsoclose.pdf

http://www.devon.gov.uk/countrymile-a361roadofsmecharacter.pdf

www.devon.gov.uk/gateway-to-north-devon.pdf

Exmoor national park background material

http://www.exmoor-nationalpark.gov.uk/learning/?a=122272

Dave Moss has a lifetime connection with the world of motoring. His father was a time-served skilled engineer from an age when car repairs really meant repairs: he ran his own garage from the 1930's to the 60's, while Mum was the boss's secretary at a big Austin distributor. Both worked their entire lives in the motor trade, so if motor oil's not in Dave's blood, its surely a very close thing.

Though qualified in Electronics, for Dave it seemed a natural step into restoring a succession of classic cars, culminating in a variety of Minis. Writing and broadcasting about these, and a widening range of motoring matters ancient and modern, gathered pace in the 1970's and has taken over since. Topics nowadays range across the modern motoring mainstream to the offbeat and more arcane aspects of motoring history, and outlets embrace books, websites national and international magazines, newspapers, radio programmes, phone-ins and guest appearances. Spare time: hard graft on the garage floor attending to vehicles old and new. Latest projects: that 1968 Mini Cooper S has finally moved again after 30 years, and when the paint is finished, the 1960 Morris Mini 850 will also soon be ready for the road again...